Treatment of molluscum contagiosum in children

Molluscum contagiosum is a viral dermatosis of the poxvirus family that causes firm, dome-shaped papules on the skin. Any child can become infected, but the disease is most common in preschoolers and elementary school children: active play, contact sports, swimming pools, and sharing towels and gadgets are typical causes of transmission. It is important for parents to understand that this is a benign and self-limiting condition. However, without treatment, molluscum contagiosum in children can persist for months or even a year, causing widespread rashes, irritation, and subsequent bacterial infection.

Morphologically, a nodule (a "pearlescent pimple" with an umbilical indentation) is the key symptom. It is painless, firm to the touch, and sometimes itchy. When pressed, a whitish, mushy mass is released—a cluster of viral particles and epithelial bodies of the molluscum. In children, it is localized to exposed skin areas: the trunk, limbs, face, and sometimes the buttocks. Mucous membranes are rarely affected. In adults, the anogenital area is most often involved, reflecting the route of transmission; in children, it is by contact with household items. In any case, a dermatologist's examination is recommended: self-squeezing injures the skin and can cause scarring and secondary inflammation.

specialists

equipment

treatment

Causes and routes of transmission of infection

The causative agent is the molluscum contagiosum virus (MCV), various genotypes of which circulate within the population. Transmission occurs through close skin-to-skin contact, through shared washcloths, towels, toys, sports equipment, and surfaces in sports facilities. Water itself does not spread the virus, but infection is often associated with swimming pools due to contact in locker rooms and on the pool deck. Microcracks in the skin, dryness associated with atopic dermatitis, and the child/teenager's habit of scratching the rash increase the risk. For families, this means simple measures: using personal towels, covering active lesions with adhesive bandages during training, and regularly changing clothing and bed linens.

Symptoms of molluscum contagiosum

The classic symptom is a smooth, pearly nodule 2–5 mm in diameter with a central, umbilicated crater. The color is flesh-colored or pinkish. The rash is painless, but can itch, which often triggers infection from scratching. When pressed, the contents are "cheesy." Inflammation around the lesion is a sign of an immune response and the beginning of regression. Fever, marked weakness, and systemic symptoms are usually absent; if they occur, another method of infection or an underlying bacterial disease must be ruled out.

In different groups:

- Children 2–10 years: torso, arms, face; Multiple elements

- Adolescents and adults: possible anogenital area

- Atopic patients: eczematization along the edges of lesions (molluscum dermatitis), frequent cases of autocontamination with Koebner lines - "chains" of nodules along the scratch line

Complications of molluscum contagiosum

Complications are rare, but possible:

- Secondary bacterial infection from scratches

- Persistent eczematization around the lesions with severe itching

- Post-inflammatory hypo- or hyperpigmentation of the skin

- Scars after traumatic removal

- Emotional discomfort in the child due to cosmetic defects and limitations in sections

- In immunodeficiency – disseminated, large lesions (rare in pediatrics, requires separate medical observation)

Diagnosis of molluscum contagiosum

The diagnosis is often made clinically based on the appearance of the nodules and their contents. When in doubt, dermatoscopy can be helpful: a central crater, radial whitish structures, and a "corona"-like vascular pattern can be seen. Laboratory tests are occasionally needed—for atypical presentations, rapid growth, eyelid localization, or suspicion of another disease.

Diagnostic methods: examination, biopsy, differential diagnosis

- Dermatologist examination. Basic method: we determine the patient's age, contact history, rate of rash onset, and the presence of itching and atopy. If necessary, gently express the contents of the element to confirm the "mush."

- Dermoscopy. A non-incidental method that allows for the visualization of characteristic structures. Better tolerated in children than invasive procedures.

- Biopsy/histology. Rare; indicated for atypical, ulcerative, recurrent lesions that do not respond to standard treatment. Histologically, molluscum bodies are present in the epithelium.

- Differential diagnosis. Common warts, milia, miliary cysts, folliculitis (bacterial infection), contagious impetigo, keratoacanthoma (in adults), and the initial stages of chickenpox. In young children, it is important to exclude genital lesions of other etiologies.

Methods of treatment of molluscum contagiosum in children

The treatment strategy is individualized and depends on age, location, number of lesions, concomitant atopic dermatitis, and social context (kindergarten, sports clubs). The goals are reasonable: to shorten the period of contagion, reduce itching and the risk of complications, maintain skin integrity, and minimize stress for the child and family. Options range from observation to removal of lesions. The decision is made by a dermatologist, who explains the pros and cons to the family.

Additionally, pain threshold and anxiety, sports participation, and home hygiene rules are taken into account. Options are discussed: expectant treatment with skin care, gentle topical agents, pinpoint removal (curettage, cryotherapy, laser), or a combination of these. Parents are given a plan: how to cover active elements, what to do if there is itching, how to prevent autocontamination. The timeframe (weeks to months) and effectiveness criteria are discussed—fewer new rashes, no skin trauma, and comfort for the child—and the need to revise the strategy if the picture changes.

Conservative therapy

A "watchful waiting" approach involves monitoring skin conditions and monitoring atopy. In most children, lesions resolve spontaneously within 6-18 months. To avoid prolonging the process and reduce contagiousness, a doctor may recommend:

- Hygiene regimen. Use personal towels, avoid scratching, and apply adhesive bandages to raised lesions during sports. This is a simple and effective method.

- Skin care. Emollients, dryness management—especially during the heating season, when itching often intensifies.

- Itch control. For perifocal dermatitis, gentle anti-inflammatory topical agents are prescribed by a doctor to break up the "itchy infection."

- Antiseptic treatment of scratches to prevent bacterial complications

When "just observing" is emotionally difficult or the lesions are actively spreading, gentle topical agents are used to gently disrupt the epithelium in the area of the nodule. It is important to strictly follow the treatment regimen and protect the surrounding healthy skin.

Surgical removal methods

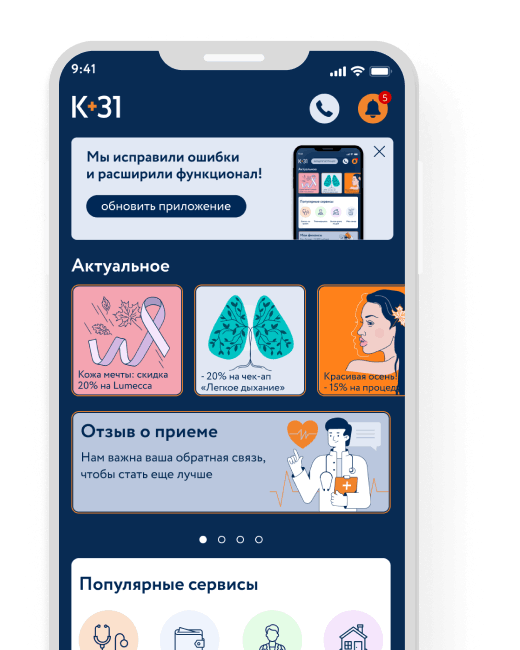

Mechanical removal reduces the period of infectivity and provides quick cosmetic results, but requires care, especially on the face and in anxious children. At K+31, we use methods tailored to the child's age and sensitivity:

- Curettage/scraping. Pinpoint extraction of the contents with a ring-shaped curette. Pros: controllability, predictability. Cons: discomfort; local anesthesia may be used if indicated.

- Cryodestruction. Short applications of liquid nitrogen. Pros: fast, on a small number of lesions; Cons: possible depigmentation, which is especially important on dark skin and in the summer.

- Laser Removal. Pinpoint treatment of the nodule, minimal trauma to surrounding tissue, good tolerability. This technique is suitable for single pimples in visible areas.

Regardless of the method chosen, mechanical intervention should be performed by a specialist physician. At-home attempts to "squeeze" a pimple often result in scarring and secondary inflammation.

Drug treatment

Topical treatments are selected individually based on the child's age, the number and location of nodules, skin type, pain threshold, and the presence of atopic dermatitis. The goal of therapy is to accelerate the natural regression of lesions, reduce itching and the risk of spreading, without damaging healthy tissue or leaving marks. Therefore, treatment always begins with a consultation with a dermatologist: they will show you how to apply the medications, how to protect the perilesional skin, how often to repeat applications, and when to take a break. It is helpful to keep a short "care diary" to monitor the skin's reaction and promptly adjust the treatment plan with your doctor.

Low-intensity keratolytics (as prescribed by your doctor) for gentle "loosening" of the nodule epithelium, while protecting the surrounding skin with zinc paste or an occlusive barrier. Gentle concentrations are acceptable, and topical application is recommended, without rubbing.

Anti-inflammatory creams for a short course of treatment for perifocal dermatitis to relieve itching and stop the "itch-trauma-new nodule."

Antiseptics – strictly for spot treatment when the skin is damaged, avoid alcohol solutions, which dry out the child's skin.

Systemic medications are typically not required in a healthy child; oral antivirals do not accelerate the regression of lesions.

Additionally: it is more convenient to apply products in the evening after washing, after softening the skin with an emollient (not directly on the nodule). Any new ointment is tested on a small area for 24-48 hours. Avoid combining several "caustic" products at the same time (acids, retinoids, harsh scrubs) – this increases the risk of burning, cracking, and depigmentation. Unauthorized cauterization, "folk" mixtures, and essential oils are contraindicated without medical supervision. If redness, severe burning, or crusting occurs, discontinue use and consult a dermatologist for a corrective action.

FAQ from parents

Should I treat it if it "goes away on its own"?

For many children, yes, but controlling the contagiousness and risk of scratching makes supervised treatment justified. The decision should be made with a doctor.

Is molluscum dangerous to health?

This is a benign viral condition. The main risks are local: eczematization, secondary infection, and cosmetic marks after injury.

Is it possible to visit the pool?

Yes, with proper hygiene and closed active areas. The pool itself isn't the "cause"; the problem is close contact in the locker room.

Is removal painful?

Modern techniques and local anesthesia make the procedure tolerable, especially when the specialist takes into account the child's age and temperament.

Our doctors

This award is given to clinics with the highest ratings according to user ratings, a large number of requests from this site, and in the absence of critical violations.

This award is given to clinics with the highest ratings according to user ratings. It means that the place is known, loved, and definitely worth visiting.

The ProDoctors portal collected 500 thousand reviews, compiled a rating of doctors based on them and awarded the best. We are proud that our doctors are among those awarded.

Make an appointment at a convenient time on the nearest date

Price

Other services

Classification and stages of development of molluscum contagiosum

Clinically, single, multiple, and disseminated forms are distinguished. Immunocompetent children typically have a limited form: from a few to several dozen lesions. In atopic dermatitis or reduced local defenses, lesions spread more frequently and form clusters.

The course of the disease can be roughly described in three stages: